Good news: You’ve got stock options, and they may have significant financial upside. Bad news, but not that bad: Unlike a cash bonus or stock grants, the decision path in front of you is a bit like Jennifer Connelly navigating the Labyrinth. I think you understand my point even if you haven’t seen the movie — options are complex. In this article, I’m going to explain, simplify and provide some rules of thumb for dealing with options.

As the title implies, I will cover the following items:

- Non-qualified stock options, aka NSOs

- Incentive stock options, aka ISOs

- Stock appreciation rights, aka SARs (these technically aren’t options, but they have a similar payoff pattern)

- Section 83(b) of the tax code (early exercise of options)

What Is an Option?

An option gives you the right but not the obligation (hence option) to buy company shares at a designated price known as the strike price or exercise price. The goal/intent is for the stock price (or market price) to appreciate while the strike price is unchanged, giving you the right to buy an increasingly valuable stock for a set price.

Options that give you the right to buy are known as call options — this is what employers grant their employees. Put options, on the other hand, give you the right to sell shares at the strike price and can be thought of as a form of insurance. We are focused solely on call options in this article — assume all instances of the word “option” refer to a call option, i.e., right to buy.

SARs are options by another name. They entitle you to the value of the stock above a certain threshold price. That excess value can be delivered in cash or stock, depending on the plan. Regardless, the payoff of a SAR mimics that of an option, with the strike price implied in the payoff pattern. Like options, you can decide whether and when to exercise and capture the value of the stock appreciation.

How Are Options Granted?

Like other forms of equity compensation, options are typically granted in blocks that vest over a pre-determined schedule. That schedule can vary, but the takeaway is that once an option vests, you have the right to exercise the option and buy shares at the strike price. Before options vest, they are of no value to you. If you leave your employer before the vesting date, it’s like having a raffle ticket and leaving before the numbers get called. You don’t get the options.

Assuming you stick around, once your options vest, you do not have to exercise them. You can hold onto them and exercise any time before they expire. A common expiration term is 10 years from grant — not 10 years from vesting, mind you — but that timing will vary by plan. If you leave your employer after vesting but before expiration, there may be a short window, often 90 days, during which you can exercise after separating employment. Pay attention to the fine print in your plan for those details. When you exercise, you pay your employer the share’s strike price. The shares are handed over and, for the most part, function like any ordinary shares from that point. You’re free to sell whenever you like or whenever you’re able if it’s an illiquid private company — more on this later.

A quick note on taxes and liquidity: To keep things simple to start, let’s ignore taxes, and let’s assume you’re able to sell shares at the market price whenever you like, i.e., they’re fully liquid. We’ll layer taxes and liquidity back into the picture later.

First Decision Point After Vesting: Should You Exercise and When?

Here’s where things get interesting — perhaps a cavalier use of the term, but just work with me. Your first decision is whether you even want to exercise (buy the shares at the strike price), and if so, when is the right time to do so?

We’ll start with an easy conclusion: You don’t want to exercise an option when the market price is lower than your strike price. Let’s say you have an option with a strike of $5, and the current market price is $2.50. Why would you pay $5 for something worth $2.50? When the market price is lower than your strike, your option is out of the money.

What about when your option is in the money, i.e., the market price is higher than your strike? Should you exercise as soon as the market price exceeds the strike price? If not, how long should you wait, or how high should you let the market price go before exercising? The “optimal” point to exercise is when you won’t leave any value on the table, and to make sure you don’t do that, for better or worse, you should understand the full value of an option. This gets a bit technical. For those without the stomach for such minutia, feel free to skip down to the summary of when to exercise. For the bold and the nerdy, let’s get into the weeds.

I’ll use a real-world example to break down the value of an option. Let’s consider a two-month call option on Alphabet stock (GOOGL) with the following details as of the time of this writing:

- Strike Price: $125.00

- Current Market Price of GOOGL: $130.21

- Option Price in the Market: $10.30

For $10.30, you can buy the option to acquire GOOGL shares for $125. If you exercised the option, you would buy a share for $125, and you could sell it immediately for $130.21, netting yourself $5.21. This is known as the intrinsic value of an option — the amount you could net if you exercised and immediately sold, or market price minus strike price.

Intrinsic value accounts for $5.21 of the $10.30 option price. What about the other $5.09? This is the extrinsic value of the option, also known as the time value of the option. It’s the expected value of all the other potential outcomes — the share price skyrocketing, tanking and everything in between. And remember, the option also gives you the ability to sit out and observe the price before doing anything, which is worth something! Once we exercise the option, we capture the intrinsic value, but we throw away the extrinsic value of the option. We don’t want to throw anything away if we can help it; we want to minimize extrinsic value before exercising.

How do we know when extrinsic value is minimized? A nerd like me (and there are more of us out there) can use the Black-Scholes option pricing model to calculate an approximate optimal point, but a good rule of thumb for when to exercise most employer-granted options is to wait until the market price is 2x–3x your strike price. At this point, the intrinsic value of the option sufficiently dwarfs the extrinsic value. Think about it using the example above. If you had a strike price of $125 and the current share price was $250, would you continue holding out for a better outcome, preserving the extrinsic value? Or would you exercise the option to capture your $125 intrinsic value? Most people would exercise and capture the significant and certain intrinsic value of the option.

For the game show and Howie Mandel fans out there, deciding when to exercise an option is a bit like a game of “Deal or No Deal.” When the offer/intrinsic value is small relative to the remaining suitcases, you’re going to keep playing — not exercise the option. Once you get a large enough offer/once your option is sufficiently in the money, you’re going to accept the offer/exercise the option, capturing the certain value (intrinsic value) and dismissing all other future outcomes (extrinsic value).

Summary of when to exercise:

- Total Option Value = Intrinsic Value + Extrinsic Value

- When you exercise, you capture intrinsic value and throw away extrinsic value. Thus, we want to exercise when the extrinsic value is minimal relative to the option’s total value, i.e., when the option is sufficiently in the money, such that intrinsic value dwarfs extrinsic value.

- Roughly, this implies you should exercise when the market price is 2x–3x the strike price, but this will vary depending on the underlying stock and attributes of your option.

Second Decision Point: What Should You Do With the Shares Once You Exercise Your Options?

Once you exercise the options, you’re holding shares in a single company, and it could be a large amount of them. There are endless data and studies that show the average single stock has a lower expected return and higher volatility than a diversified portfolio. If you liquidate the shares immediately, you could: 1) use the proceeds as you would other income for budget needs or 2) reinvest in a diversified portfolio.

If you want to keep the shares for some reason, limit it to an amount that’s not going to have a ruinous impact if things go south — say 5%–10% of your investable assets, which will vary across individuals. But as with all individual stocks, I would caution against overconfidence. We’re getting beyond the scope of this article, but reliably picking stocks that beat diversified indexes is very difficult if not impossible to do sustainably.

One glaring exception to this “sell immediately” conclusion may arise in the case of ISOs, where a certain holding period qualifies you for more favorable tax treatment. If the position and gain are large enough, it might be worth risking the volatility of a single stock to hold out for significant tax savings. More on this later.

Taxes, of Course

Taxes are a bit complex when it comes to options. Tax treatment is what separates NSOs and ISOs. Let’s illustrate using an example:

Assumptions:

- Strike Price: $4 — This is the purchase price guaranteed to you.

- Market Price at Exercise: $15, i.e., the share price has appreciated significantly, and you decide to exercise and buy shares.

- Bargain Element: $11 — When you exercise, you pay $4 for a share worth $15. This $11 difference is the bargain element.

- Ultimate Sale Price: You eventually sell your share for $16, which makes your total gain $12, i.e., $16 – $4.

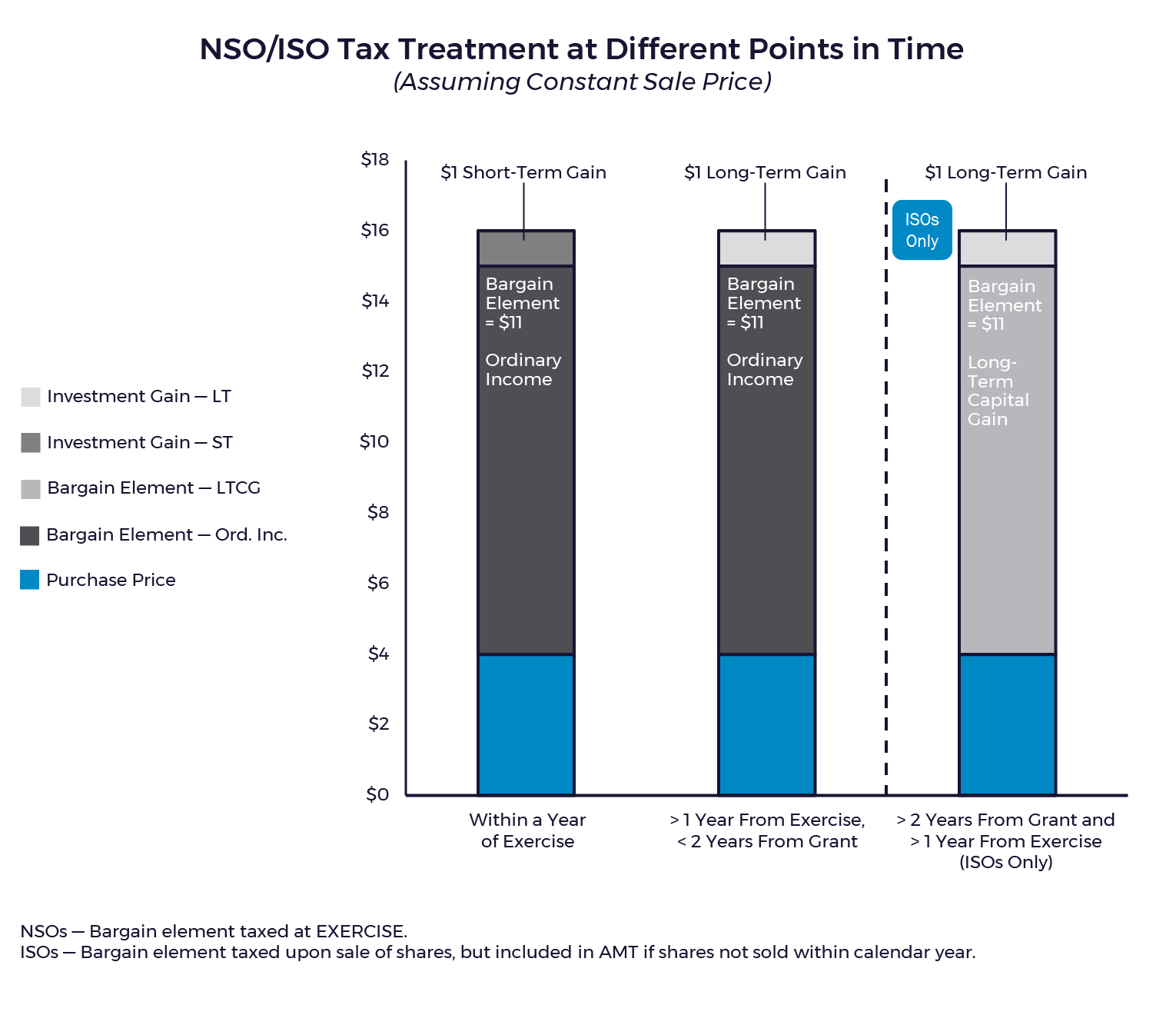

The tax treatment of that $12 gain depends on when you execute each step of the process. Let’s use this chart to guide the discussion:

The tax treatment depends on the type of option and when your transaction occurs:

- If you exercise and sell the shares within one year of exercising (left bar), the bargain element of $11 is taxed as ordinary income. The investment gain of $1 is a short-term capital gain, which will also be taxed at ordinary income rates. In other words, the full $12 gain is taxed as ordinary income.

- If you exercise, hold the shares for more than a year, and sell within two years of the grant date, now your investment gain of $1 turns to long-term capital gains, but the bargain element of $11 is still taxed as ordinary income. In other words, $1 of your $12 total gain is now long-term capital gains, and $11 is still ordinary income.

- The final bucket (right bar) is applicable only for ISOs. If you exercise and hold the shares for at least a year from exercise and at least two years from the grant date, the entire gain of $12 is now long-term capital gains, i.e., in the column to the right. This is what’s so advantageous about ISOs — the bargain element becomes a long-term capital gain.

Tax timing: With NSOs, the ordinary income tax on the bargain element is due at exercise. This is an important cash-flow consideration if you plan to exercise NSOs and keep the shares. Not only will you need the cash to exercise, but you will also need cash to pay the tax bill. Once you’ve exercised (and paid the tax), a share from the NSO is like any other share purchased in the market — any taxes on gains are due upon sale.

With ISOs, whether you hit the window for ordinary income treatment or hold out for long-term cap gains treatment, the tax on the bargain element is not due until sale — another advantage of ISOs. However, the bargain element is included in your Alternative Minimum Tax (AMT) calculation in the year of exercise, assuming you don’t sell the shares within the same calendar year. If you’re unfamiliar with AMT, it’s another method of calculating your tax bill that includes and excludes items from the traditional calculation method. The AMT could result in a larger tax bill if the bargain element on your exercised ISOs is very large relative to your other income.

Excess tax paid under AMT becomes an “AMT credit” and will be credited against capital gains at the ultimate sale of the transaction, which means this is somewhat of a timing issue as opposed to overall higher taxes. You should speak with a tax professional for the details, but regardless, even if you get it back eventually, AMT is an additional cash-flow consideration when you exercise ISOs.

What about stock appreciation rights? A stock appreciation right effectively entitles you to the bargain element whenever you decide to exercise. In this example, let’s say you exercise/cash in when the market price is $15. Rather than you paying the company for shares, the company will simply pay you $11, i.e., the bargain element. That payment can be in cash or in $11 worth of company stock. In either case, it’s taxed as ordinary income. If it’s paid in shares, the shares are like any other, you can liquidate immediately and use the cash as you would other income for spending or investing in a diversified portfolio. If it’s cash, there’s no decision to be made — it’s similar to getting a bigger paycheck.

Tax Wrinkle: Section 83(b)

As if we weren’t having enough fun — let’s add a tax code reference to the mix. Section 83(b) is known as the right to early exercise — exercising options (buying shares) before your options are vested.

The goal of exercising early is to reduce the size of the bargain element and thus your tax bill. Going back to our bar chart example, if you’d exercised when the market price was $10 instead of $15, with your $4 strike, the bargain element would be $6, not $11. With NSOs, the bargain element is always taxed as ordinary income. Assuming the same outcome as above, ultimately selling your share for $16, you’ve reduced the portion of your total gain subject to ordinary income taxes from $11 down to $6, shifting that $5 portion of your total gain to be treated as capital gains.

There are risks in electing 83(b) and exercising early. Remember, this means you’re buying the shares before they’ve vested. If you leave the company before they vest, you could be out your shares, and though the company does return your strike paid, you don’t get a refund for the taxes paid. There’s also a risk the stock price tanks before they vest, which means you could have had a lower tax bill had you waited, or maybe you’d have changed your mind entirely about purchasing the shares.

Should investors exercise 83(b)? There’s no scientific answer. For NSOs, early exercise could save a lot of taxes if the stock does well, but if it does poorly, you pay a tax bill for something that could end up worthless. If it were me, I’d balance the risk and consider only a small portion for early exercise. With the rest, I would stay on the sidelines and exercise only if/when the stock does very well, even if it means a higher tax bill than if I’d exercised early.

For ISOs, the early exercise incentive is diminished, as these get favorable tax treatment with a long enough holding period after exercise. I’d rather wait and take risk on a more mature company after the stock has already done well. You still get the cap gains tax treatment on the entire gain if you hold the shares long enough. There may be different reasons for exercising ISOs early, but for the most part, there’s little incentive to take the risk up front when you can get the same benefit by holding the stock later.

And with stock appreciation rights, 83(b) is not applicable. Sometimes it’s nice not to have a choice.

And Last but Certainly Not Least, Liquidity and Private Company Shares

Thus far, we’ve assumed shares are completely liquid. That is almost always the case for publicly traded companies, but it’s more complicated for private companies. The secondary market for private shares has grown to a point that it’s often possible to sell your private shares or options, but it’s certainly not as easy as logging into your account and hitting the trade button. It can take weeks with many fees baked into the process and may involve attorneys and accountants.

A few things to keep in mind for private company options:

- Cash required for purchase: Don’t forget, with options, you have to pay the strike price. Even if the shares are worth far more than your strike (options are deep in the money), you may not be able to sell the shares after exercise. You have to wait for liquidity.

- Cash required for taxes: If you exercise NSOs, in addition to the cash required for exercise, you owe ordinary income tax on the bargain element. If you can’t sell shares to raise cash to cover that bill, you’ll have to come up with cash elsewhere. Analogously, with ISOs, if AMT is triggered and you can’t sell any shares, you’ll have to get the cash elsewhere.

- Company valuation volatility during illiquidity: Cash considerations aside, if you’re sitting on illiquid shares, the value of those shares could always change, sometimes significantly, before you’re able to sell. The nice thing about options is that you can wait for more clarity before having to pony up any cash.

Conclusion

To sum up navigating ISOs, NSOs, and SARs:

- When to exercise: Wait until the market price is ~2x–3x your strike price before considering exercising.

- When to sell after exercising: With NSOs and SARs where you’ve been granted shares, sell shares immediately. With ISOs, if the bargain element is sufficiently large, it’s likely worth holding for a year from exercise and two years from grant for full capital gains treatment.

- When to elect 83(b) early exercise: This is not applicable with SARs. With ISOs, early exercise is probably not worth it. With NSOs, you might want to do a small portion of early exercise to save taxes in the event of a good outcome, but there’s a lot of risk in doing so. No shame in waiting for the stock price to appreciate.

- Constraints and nuances to keep in mind: The biggest constraint to keep in mind is liquidity. Even if it’s “optimal” to exercise based on your option and market prices, liquidity constraints may mean you need to wait or exercise only a portion of your options. The other constraint to bear in mind is cash flow. With options (not SARs), exercising involves a cash outlay for the purchase and for any resulting tax bill. The bargain element is taxed immediately for NSOs. The bargain element is not taxed for ISOs until you sell the shares, but if you hold them, this is included in AMT. Either one of these tax liabilities could be particularly challenging if the purchased shares are illiquid.

Suffice it to say, if you’ve been granted employee stock options, you have a lot of … options. Hopefully, mediocre humor aside, this piece has shed some light on how to navigate the many decision points when considering how to handle NSOs, ISOs and SARs.