With the one-year Treasury yield approaching 5.50%, I am not surprised that some clients are asking if now is the time to move to Treasuries. My reply is consistent: It depends, but not on the market.

If you have an impending need for cash within the next one or two years, for example, to buy a car, purchase a home or cover expenses while you start a new business, then moving some cash to T-bills could make sense to reduce market risk on money that you need in the short term. However, for the long term, moving cash out of a well-constructed and diversified stock and bond portfolio could cost millions.

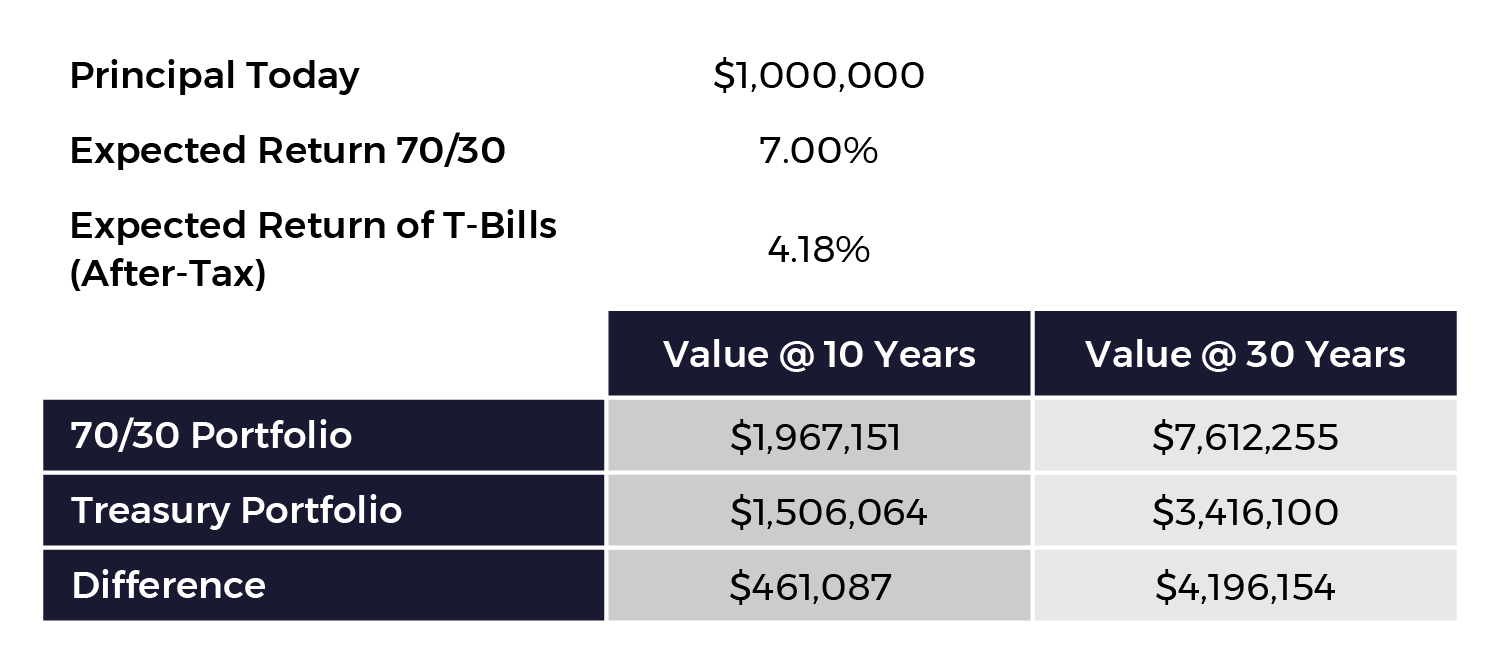

For the sake of round numbers, if we assume a $1,000,000 investment, moving your portfolio from a 70% equities/30% bond portfolio to 100% Treasuries will likely cost you $450,000 over 10 years and more than $4,000,000 over 30 years; that is 4x your current principal. This is because the after-tax and after-fee expected return for a 70/30 portfolio using low-cost ETFs and index funds is about 7.00%.

In contrast, earning 5.50% for T-bills or money markets seems attractive, for effectively minimal risk, but that is a pre-tax number. Interest income is taxed at ordinary income rates, so if an investor has an effective federal tax rate of 24%, the after-tax return drops to 4.18%. If we just compound annually at those after-tax rates, assuming no contributions or withdrawals, the math shows a tremendous discrepancy in outcomes in the long term.

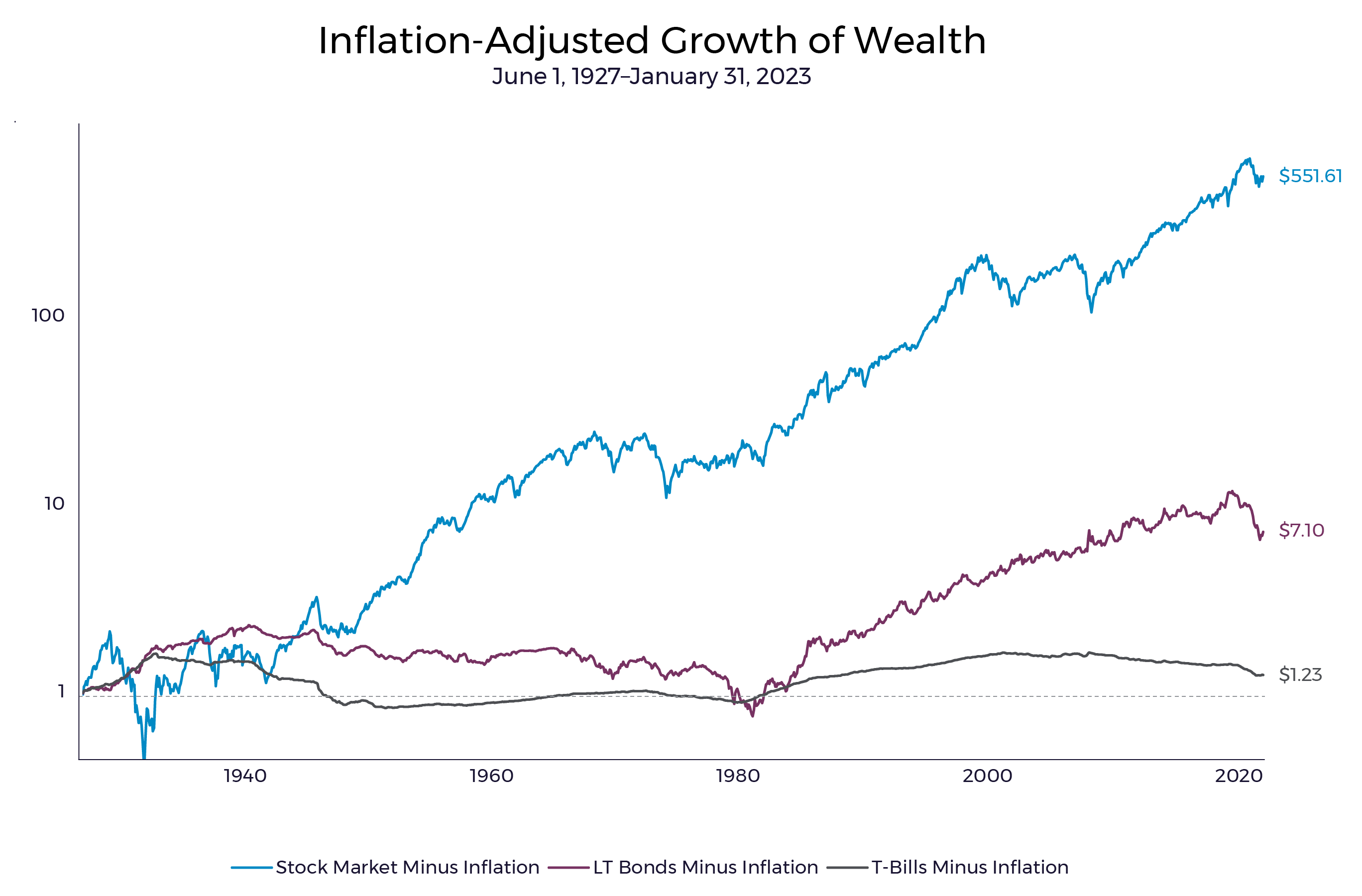

The above example also assumes that Treasuries will continue to yield 5.50% through the longer-term investment period, when in reality they fluctuate, and current market signals indicate a fall in short-term Treasury rates in the next few years. While some may shrug and plan to re-enter the equity markets when rates fall, market timing rarely ever works in part because you have to be right on the way out and the way back in. We can look through history and see that a T-bill-only investment approach will at best maintain your purchasing power over inflation but will not increase it and hence will not afford most of us to meet our retirement cash flow needs. It does not matter whether T-bill rates are 0%, 5%, or 10% like they were around 1980.1 The Treasury rate sets the risk-free rate, and over the long term, stocks and bonds earn more because investors get compensated above the risk-free rate for taking risk.

The chart above further highlights the importance of keeping equities and even long-term bonds in the mix. Long-term investing in the equity and bond markets can offer investors a return that outpaces the effects of both inflation and taxes; T-bills do not. This is because risk and return are directly related. Investing on emotions and market timing rarely ends well. If you are thinking of moving to T-bills, we suggest you consider your long-term investment horizon, stay disciplined and only move some cash to T-bills if you have a clear need for the cash in the short term.

SOURCE

1 “Historical Returns on Stocks, Bonds and Bills: 1928–2022.” January 2023.