You’ve got equity compensation! What now? It’s a little bit like having the ingredients for a gourmet meal — it has potential to turn out great, but it could still go a lot of ways. Unlike a regular old paycheck, you have some decisions to make, and those decisions will impact the ultimate value of this compensation. Thankfully, with an understanding of how these instruments work and how they’re taxed (sorry, taxes are boring but relevant, like always) we can come up with some loose rules of thumb.

There are many forms of equity compensation. To keep things manageable, I will limit this piece to two common forms of equity compensation and provide guidance as to how I would deal with them:

- Restricted Stock Units aka RSUs

- Employee Stock Purchase Plans aka ESPPs

Restricted Stock Units aka RSUs

What are they? RSUs are company shares given as compensation. Employers often grant them in blocks that vest over a predetermined schedule. Sorry, fashionistas — vesting, in this case, has nothing to do with the sleeveless garment. Vesting is when you own the shares, and usually at that point, you can choose what you want to do with them, i.e., sell or hold.

RSU Vesting Explained

In a publicly traded company, vesting is based on one requirement — time. Vesting schedules can be cliffs, where the shares vest all at once on a certain date. They can also be pro rata, where shares vest gradually over time. They can also be some combination of the two. A common vesting schedule is four years with a 25% cliff after one year and pro rata monthly thereafter. For example, for 100,000 RSUs, after one year, 25,000 shares would vest. After that point, the remaining 75,000 shares would vest proportionately over the remaining 36 months, or approximately 2,083 shares per month.

Once the RSUs vest and you receive the shares, they function very similarly to shares you buy on the open market. The one exception is that many employees have trading restrictions around earnings announcements and other insider-information events; thus, you might not be able to sell these at the drop of a hat. One way around the restricted trading period is an automated selling plan under which you set a schedule to sell shares ahead of time, and that schedule cannot be adjusted once put in place. Not all employers or plan administrators will offer this, but it’s worth investigating.

In a privately held company, in addition to the time requirement described above, vesting may also depend upon a liquidity event such as an IPO or acquisition. This time and liquidity vesting logic for private RSUs is sometimes called “double-trigger” vesting.

Once vested and delivered, these also operate as normal shares subject to the usual capital gains taxation. If there is only a time requirement for vesting, the company may still be private when the shares are delivered to you, and the shares will be a lot less liquid than those of a public company. You don’t have control over this, but it’s something to bear in mind, particularly for paying your tax bill on vested shares – more on this later.

With either public or private company RSUs, if you leave the company before the RSUs vest, they disappear.

How are they taxed? Everyone’s favorite topic. The market value of the RSUs on the delivery date is taxed as ordinary income. Sidebar — The delivery date is almost always the same as the vesting date, but in rare cases, shares are delivered at some point after the vest date, in which case, tax is assessed on the value at the delivery date. Because that’s rare and to keep things simple, I’m going to use “vested” and “delivered” interchangeably, just be aware there are instances where this isn’t the case.

You are taxed on the vest price whether you sell the shares or not. Assuming the share price is $5 on the vesting date, the company is handing you something worth $5; it makes sense that it’s taxed the same as cash would be. Effectively, RSUs are like salary from a taxation standpoint; it just happens that instead of cash, you receive stock. Often, a company will withhold taxes from the vesting stock by holding back a portion of the stock, akin to withholding from cash salary.

I recommend paying attention to how much is withheld and discussing with a tax professional to ensure it’s the right amount. There’s nothing worse than getting an unexpected (and potentially large) tax bill.

Once vested (and delivered), the taxation of your shares functions similarly to any other shares, as I stated above. If you sell within a year, the gain from the vest price is treated as a short-term capital gain and taxed equivalently to ordinary income rates. If you hold for a year or more before selling, the gain qualifies as a long-term capital gain, which is generally a more favorable tax rate.

What about the grant price? I haven’t even mentioned grant price yet, and there’s a reason for that. It’s because it doesn’t matter. The grant price is the stock price on the day the company grants the RSUs. It’s used to approximate the level of compensation they want to … grant. However, once the RSUs are granted, the grant price does not matter. The only things that matter after that point are:1) the vest price and 2) how the stock performs thereafter, assuming you choose to hold the shares or are forced to hold them. If the company issued you 10,000 RSUs at a grant price of $5, do not anchor yourself on earning $50,000! If the stock price at the vesting date has halved to $2.50, you only get $25,000 worth of stock. For the sake of your mental and financial health, forget about the grant price!

What would I do with the shares once the RSUs vest? I’d probably sell them immediately. Given the shares’ market value on the vest date is taxed as ordinary income, keeping the shares is equivalent to receiving the same amount of cash compensation and immediately using all of it to buy company stock. By and large, this is not a good idea! Research shows us that individual stocks are volatile and, on average, lead to worse long-run returns than a diversified portfolio — more detail in the next paragraph.

Think of a case where you receive $50,000 in equity compensation, paying full ordinary income tax on that amount, and three months later, the shares are worth $40,000. You paid tax on $50,000 and now only have $40,000 to show for it. Thus, I would sell the shares immediately after vesting, and either treat the proceeds as cash compensation (for budgetary needs, etc.) or reinvest in a diversified portfolio.

This will be more complicated if you have shares in a private company. There may be opportunities to sell on secondary markets, or you might be stuck holding the shares until a liquidity event.

If you’re reading my advice and thinking, “Well, that’s kind of boring, Steve. I want to hold the stock when it goes to the moon!” I got news for you: 1) I’m a boring guy and 2) I’d caution you on that “to-the-moon” theory. Building wealth is about being the tortoise, not the hare.

Is there a chance your company stock goes to the moon? Yes. There’s also a chance you buy a winning lottery ticket or that I literally go to the moon for my next vacation, but those are not the expected outcomes! In a study on concentrated stock positions, JP Morgan found that more than 40% of stocks in the Russell 3000 Index (a proxy for all U.S. stocks) have experienced a “catastrophic stock price loss” since 1980, defined as falling 70% from their peak and never recovering.1 Since 1980, 42% of stocks in the Russell 3000 have had negative absolute returns. Further, a full 66% of stocks underperformed the index, highlighting how hard it is to outperform a diversified portfolio. We want to be the casino, not the gamblers — we take the odds that are in our favor and accumulate wealth over time via a diversified portfolio.

After all that, if you’re still wanting to hold onto the shares, limit it to a level that’s not going to ruin you if it crashes. Usually, we say that limit is about 5% of investable assets, but that limit varies based on individual circumstances.

RSU Summary

What they are: Shares in the company given as compensation.

How they’re taxed: The market value of shares on the vest date (or the delivery date, if it’s later than vest) is taxed as ordinary income. Thereafter, the tax treatment is similar to that of any other shares – short-term capital gains if held less than one year and long-term capital gains if held for one year or more – with the cost-basis being the vest price (or price at delivery). Remember that the grant price is all but irrelevant. It has no impact on taxation or your ultimate compensation.

What to do with them: Given the volatility and lower expected returns of single stocks relative to a diversified portfolio, for most people, the most sensible thing to do is sell immediately upon vesting/delivery and re-invest in a diversified portfolio.

Employee Stock Purchase Program aka ESPP

What is it? I’m sorry to disappoint fans and supporters of the paranormal, but this has nothing to do with ESP, that magical sixth sense of clairvoyancy and mind reading. That would certainly be a “nice to have” in this realm, but alas, here we are, sans crystal ball. Nonsense aside, an ESPP isn’t quite as generous an RSU program. Instead of simply giving you shares, your employer allows you to buy them at a discount, oftentimes 15%. Yes, you have to pay for the shares, but nonetheless, the discount is still free money.

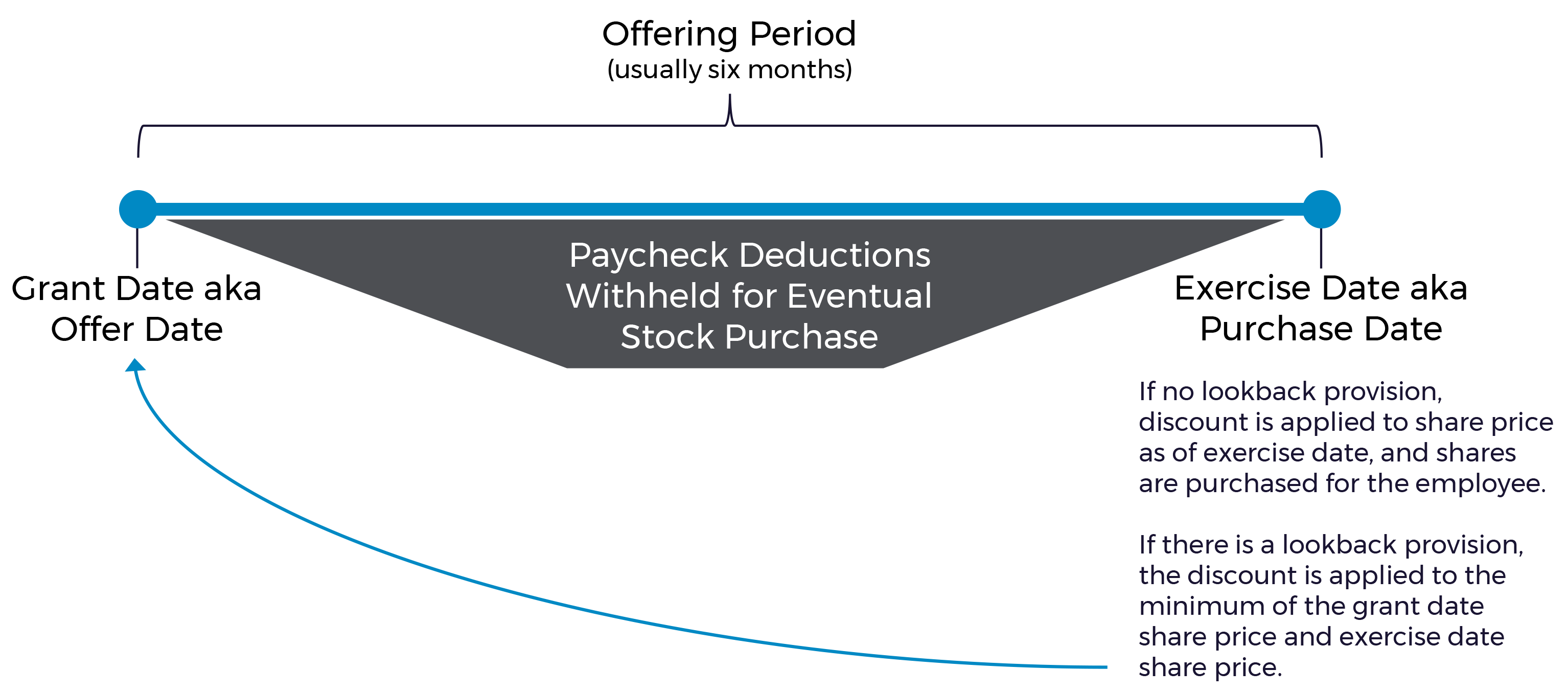

A typical ESPP operates as follows: An employee opts in during an enrollment period before the offering period. There are usually two offering periods per year, six months each per period. The start of the offering period is called the grant date or enrollment date; the end of the offering period is referred to as the exercise date or purchase date. Contributions to purchase the shares are made via paycheck deductions during the offering period. At the end of the offering period, the shares are purchased. The discount (and hence, the purchase price) may apply to the market price at the grant date, or if there is a lookback provision, the discount would apply to the price at the grant date if it’s lower than the exercise date price.

Finally, there is a limit to how much you can contribute to an ESPP. The IRS limits your annual ESPP purchase to $25,000 based on the market value on the grant date. Thus, if the market value at the grant date is $25/share, you’re limited to 1,000 shares ($25,000 at $25/share) regardless of your discount or the market price on the exercise date. If the price declines between the grant and exercise dates, you cannot buy more shares – the limit is based on the market price at grant date. In addition to the IRS limit, your employer may have internal limits in place for how much stock can be purchased through the ESPP. Of course, you will be subject to the stricter of the two limits.

How are the shares taxed? First of all, at the time of purchase, your employer will withhold taxes from your contributions and purchase the shares for you. At that point, no other taxes are due. After that, there are several holding period breakpoints that determine the taxation of shares purchased through an ESPP. This gets pretty hairy, and I’m going to attempt the miracle of explaining this without making your eyes glaze over. Buckle up! Alternatively, if you’re not a believer in miracles or your eyes glaze easily, you can skip these details and scroll down to where I tell you what I would do.

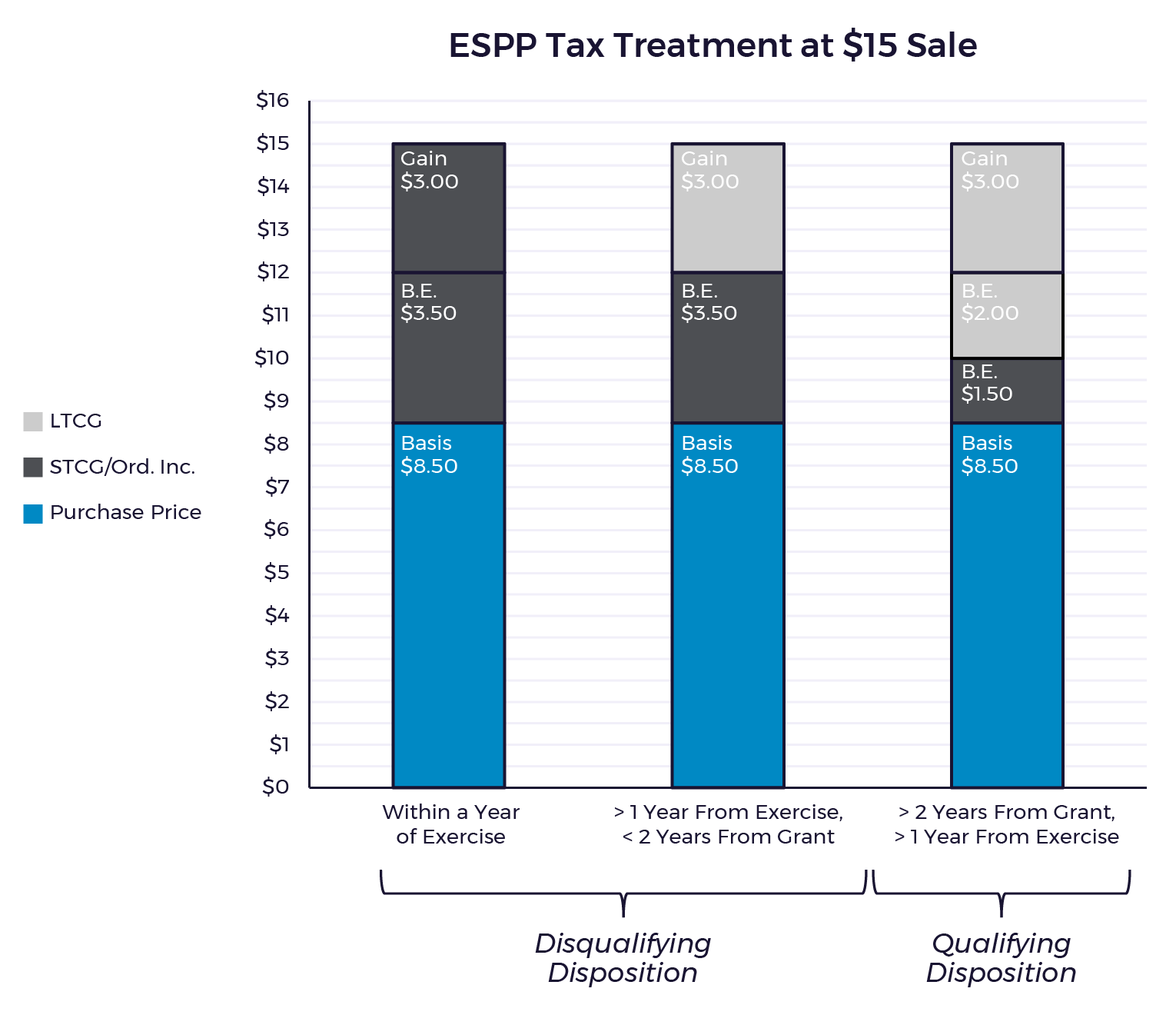

Let’s assume the stock price on the grant date is $10 and $12 on the exercise date. Your employer buys the stock for you for $8.50 per share (assuming there is a lookback provision, the 15% discount applies to the cheaper of the two prices).

There are three distinct holding periods that impact taxation:

Time Period 1: You sell within one year of the exercise date. Say you sell the shares for $15 each. You have $3 of short-term gains ($15 – $12), and the $3.50 “bargain element” ($12 – $8.50) is taxed as ordinary income.

Tax summary: Your entire profit of $6.50 per share is taxed at ordinary income rates.

Time Period 2: You sell one year after the exercise date but within two years from the grant date. Keeping with our $15 selling price assumption, now your gain of $3 ($15 – $12) is taxed as long-term capital gains, but the $3.50 bargain element is still taxed as ordinary income.

Tax summary: You’ve effectively moved $3 of your $6.50 total per-share profit to long-term gain treatment; the remaining $3.50 is still taxed at ordinary income rates.

Time Period 3: You sell more than two years after the grant date. This gets a little tricky. First, your ordinary income is the lesser of:

- Your gain as calculated by selling priceminus actual price paid, i.e., $15 – $8.50 = $6.50, or

- The employer’s discount, i.e., $10 – $8.50 = $1.50

Thus, ordinary income per share sold in this case is $1.50, the lesser of these two numbers.

The gain portion is calculated as [selling price minus actual price paid minus the ordinary income portion we just calculated], i.e., $15 – $8.50 – $1.50 = $5, and this is treated as long-term capital gains.

Tax summary: You’ve effectively moved $5 of your $6.50 total per-share profit to long-term gain treatment; just $1.50 is taxed at ordinary income rates.

Below is a visual of the above examples. B.E. = bargain element.

In short, the longer you hold the shares, the more of your profit gets treated as long-term capital gains as opposed to ordinary income.

You might hear of qualifying dispositions or disqualifying dispositions. These are official names for holding periods. As labeled above, if you sell within two years of the grant date (time periods 1 and 2), it’s a disqualifying disposition. If you wait two years from the grant date AND one year from the purchase date to sell, it’s a qualifying disposition.

Most ESPPs are qualified plans, which is what I’ve presented here. These are eligible for qualifying dispositions, which may offer better tax treatment on a part of the bargain element. Some employers offer plans that are non-qualified, and as one might expect, those are not eligible for qualifying dispositions. The bargain is taxed as ordinary income at purchase/exercise, and the shares thereafter are like any other shares. In the visual aid, the last bar is irrelevant for non-qualified plans.

What would I do with an ESPP? The first question is whether to participate, and the answer is yes, assuming I can afford the paycheck deductions for six months. It’s free money. The second question is what to do with the shares once you have them. My default path would be to keep it simple — sell the shares immediately after purchase. Yes, my gain will be taxed as ordinary income, but this is guaranteed money. Assuming your discount is applied to the grant price, you’re effectively paying 85 cents for a share and selling it immediately for a dollar. That’s an immediate and risk-free gain of 17.6%!

Holding longer than that is a trade-off, and maybe even a gamble. Yes, if you hold the shares long enough, you can get more favorable tax treatment. But the risk is that you’re holding a single stock, and single stocks can be volatile. Refer back to my comments in the RSU section — historically, the average stock underperforms the market, and a large portion have had negative returns.

ESPP Summary

- What it is: An ESPP allows you to purchase shares at a discount.

- How it’s taxed: Taxation of shares purchased through an ESPP changes through three phases: 1) less than one year from purchase, 2) greater than one year from purchase but less than two years from the grant date and 3) greater than one year from purchase and two years from grant date. The further you go into these breakpoints, the more of the gain you can push to long-term capital gains, which is likely more favorable than ordinary income tax rates.

- What to do with it: Keep things simple and lock in the “free money” (courtesy of the discount) by participating in the ESPP and immediately selling the shares. This is the least favorable tax treatment, but holding out for better tax treatment risks the volatility of a single stock and exposes you to the possibility of having shares worth less than you paid for them.

Conclusion

A big thank you to all who have read this — and a big congratulations to those who did it without falling asleep! To revisit my gourmet meal ingredients analogy from the start of this article, maybe you’ve attended Le Cordon Bleu of Equity Compensation and can whip up the proverbial batch of financial cake batter with your eyes closed. But if not, it might make sense to consult with a professional chef — a financial advisor, to make the analogy very clear — to help you put all the ingredients together in a way that suits you.

SOURCE

1 Michael Cembalest, Kirk Haldeman, Chris Baggini and Jake Manoukian, “The Agony & the Ecstasy (Eye on the Market).” JP Morgan Asset Management, March 15, 2021.